January 13, 2024 – FMN was able to kick-off the stewardship activity to replace and monitor the Blue Bird Boxes at River Farm.

FMN Susan Farmer with Bob Farmer

Susan Farmer is the FMN coordinator for service and citizen science activities at River Farm. When the American Horticultural Society (AHS) notified her that the donated boxes were in, she organized FMN volunteers to help Jack, the River Farm groundskeeper, with installation. Eight boxes were replaced and ten sad boxes were removed and salvaged for parts.

The long-term plan is to officially monitor and maintain the boxes. To officially monitor and report hours to the Virginia Blue Bird Society requires training, so Susan is arranging that for early March. Susan is also creating a presentation for an FMN CE program. Along with general history of bluebird trails and how they have helped bring back the bluebird, she will discuss specifics on the River Farm opportunity.

Parts in the cart for 8 boxes – photo Jerry Nissley

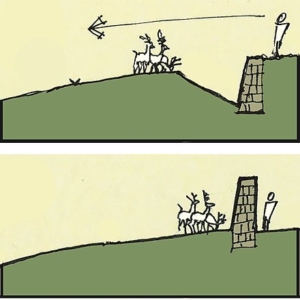

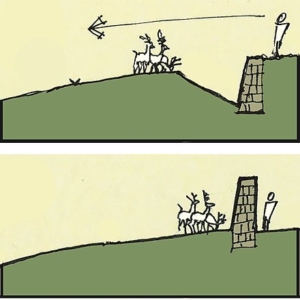

As an aside to this … notice the Ha-Ha Wall (or saut de loup) behind the chain in the river view photo. You don’t see it? That is precisely the intended illusion. These walls are a feature developed by the French in the 1600s. Chateaus and estates would incorporate Ha-Has in landscape design to prevent access to a garden by, for example, grazing livestock, without obstructing pastoral views. I’ve seen these now at Gunston Hall, Mount Vernon, and here. River Farm was once owned by George Washington.

Crude illustration of a Ha-Ha -graphic by WikiMedia Commons

For the garden design enthusiasts among us … the name Ha-Ha was first used in print in Dezallier d’Argenville’s 1709 book, The Theory and Practice of Gardening. He explains that the name derives from the exclamation of surprise viewers would make on recognizing the optical illusion.

Mount Vernon incorporates Ha-Has on its grounds as part of the landscaping for the mansion built by George Washington’s father, Augustine Washington. President Thomas Jefferson built a Ha-Ha at the southern end of the South Lawn of the White House, which was an eight-foot wall with a sunken ditch meant to keep the livestock from grazing in his garden. Yes, livestock used to graze the White House lawns.

A Ha-Ha view – photo Jerry Nissley

A 21st-century use of a Ha-Ha is at the Washington Monument to minimize the visual impact of security measures. After 9/11 and another unrelated terror threat at the monument, authorities put up jersey walls to prevent motor vehicles from approaching the monument. The temporary barriers were later replaced with a new Ha-Ha, a low 30 inch granite stone wall that incorporated lighting and doubled as a seating bench. It received the 2005 Park/Landscape Award of Merit.

FMNs Kristin, Susan, Donna, Sarah, Jerry, Monica, and Paul – photo Jerry Nissley

But I digress … we had a great winter’s day start to this wonderful stewardship opportunity at River Farm. Thank you to the 7 FMN that helped Jack on installation-day. We look forward to working with other volunteers and staff to learn more about River Farm and grow this partnership in 2024.