Article by FMN Stephen Tzikas

Reprinted from Virginia Bluebird Society The Bird Box, Spring 2022, with permission.

In 2021 I volunteered to be a bluebird monitor at Langley Fork Park in McLean, Virginia. It is one of many citizen science programs promoted by the Virginia Master Naturalists and managed by the Virginia Bluebird Society (VBS). As a Chemical Engineer I have various interests in the physical sciences and engineering. As I get older, I am interested in getting more exercise, and one way to do that is to combine it with a life science that requires outdoor exposure. Since I am partial to birds because of a childhood pet parakeet, I decided to monitor bluebirds. Monitoring a bluebird trail and entering the data into Cornell University’s NestWatch was a rewarding new personal experience. At the end of the season, about August 2021, I finally reviewed the NestWatch data and correlated it to my experience of monitoring the trail. It was an extraordinary successful season. I decided to speculate as to why the season’s success was extraordinary.

The Site and the Monitoring Team

Langley Fork Park is 52 acres with a latitude of 38.9 degrees and a longitude of -77.2 degrees. The 10 bluebird nest boxes in the park are evenly distributed along the perimeter of the tree/field boundary. They all have stovepipe baffles and Noel guards. I monitored this trail with Naveen Abraham (trail leader) and Cindy Morrow. We shared our findings every week and had plenty of interactive time with the nests and birds. Our trail leader started monitoring the trail in 2016, the year that data collection for the trail began in NestWatch. However, the trail had been monitored for 10+ years prior to that.

The Results

Author checks box 9. Photo: Ako Tzikas, 5/30/21

In the 2021 season, we had 3 types of nesting birds. Apart for one late but successful nesting attempt by house wrens, the season was dominated by eastern bluebirds and tree swallows. Since 2016, the only other species making use of the nesting boxes was the Carolina wren. The count of 63 fledglings was quite a successful number compared to that of prior years. The NestWatch site sums a total egg count, as well as the total fledgling count. Although we counted eggs and fledglings as best as we could, it was not always possible to count all eggs as the view was obstructed, nor could we always count fledglings accurately as they could be piled on each other. The total number of fledglings, therefore, is a minimum counted number. It could be slightly higher, as indeed it was evident from the bluebird egg count, which was 29 eggs compared to the 26 recorded fledglings. Although we lost a bluebird egg due to predation, one can see a remaining discrepancy of 2, which I believe favors 2 additional fledglings. Likewise, the count of tree swallow eggs (16) were obviously undercounted because of obstructions like large nest feathers. Although we lost 4 eggs due to predation, the total number of fledglings was 33. This leads to small inconsistencies in the NestWatch data and the automated calculations. For this reason, I would recommend that nest monitors make a good effort to count precisely, as well as document in the NestWatch comments the perceived situation for the benefit of other researchers. Nonetheless, the small discrepancies did not prevent an analysis. Finally, together with the accurate count of 4 house wren eggs and a corresponding 4 fledglings, one arrives at the sum of 63 fledglings. We had 17 nesting attempts at the 10 boxes.

For context, the six seasons of monitoring (2016 through 2021) saw 77 next attempts for the 10 boxes, with a sum of fledged at 208 for all species. Of these fledged species, bluebirds accounted for 48, tree swallows for 127, and the balance between house wrens and Carolina wrens. Consequently the 26 bluebird fledglings in 2021 represents 54% of all 48 bluebird fledglings since 2016. This was indeed an outstanding success.

Analysis

Bird populations have been decreasing worldwide, and along with it important ecosystem processes such as pollination and seed dispersal. To date, the number of birds is estimated to have been reduced by up to 25 percent in overall numbers. It is encouraging then when organizations like the VBS help boost those populations. The VBS trains and organizes volunteers to monitor nest boxes. was fortunate to be able to experience the success of the 2021 bluebird season at Langley Fork Park. As I speculated on the reasons for the success, my investigation consisted of the following areas of review: trail leader management; weather; and food availability.

Last year (2020) was a very disappointing year at Langley Fork Park as there were no successful bluebird nests. Almost every box had tree swallows to start, and later in the season there were a couple of house wren nests. There was only one bluebird attempt, but that attempt was ended by a house wren which poked holes in the bluebird eggs and removed them from the nest. In 2021 we moved a few boxes by a little bit in the beginning of the season. This made all the difference in helping to create a more favorable nest site habitat for the bluebirds. We discussed some possible standard types of actions that could improve the locations for nesting. We decided to move boxes #3, #6, #7, #8, #9 and #10. Afterwards, it was these boxes that the bluebirds embraced, i.e., boxes #3, #6, and #8. Bluebirds also nested in box #7 initially, before a tree swallow evicted the bluebird with the loss of an egg.

When I started monitoring the bluebird trail, I noted everything I saw, including other nearby wildlife, such as foxes. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I

Box 9 Sparrow spooker. Photo: Stephen Tzikas, 5/5/21

was documenting potential predators. But the noticeable issues of predation came from other bird species instead. We lost a male bluebird in Box #8, though we were not sure how it was killed when we found it’s body in the nest box. Nor did we know what species of bird was responsible for it. We don’t know if the bluebird was attacked in the nest box, or sought refuge in it after a struggle outside the box. As noted, we also lost a bluebird nest box with 1 egg when it was taken over by a tree swallow family. Finally, one tree swallow nest was abandoned when its eggs were attacked and damaged. Other than that, we did not have much predation except for some assertive house sparrow attempts at competition in the beginning of the season. To frighten the sparrows away, we successfully used a spooker. Finally, the last aspect of this season’s trail management was the quick elimination of an ant infestation in a couple boxes.

Weather in the form of temperature, precipitation, and snow can clearly play a role in the health and number of birds. With Langley Fork Park being about 3 miles from the Washington DC boundary line, I reviewed historical weather data from Washington, DC from the NOAA and National Weather Service. A precipitation link offers monthly, seasonal, and annual average data back to 1871, plus a comparison to the norm. It shows a significantly wetter season in 2021, and the data can be accessed here: https:// www.weather.gov/media/lwx/climate/dcaprecip.pdf. A temperature link likewise offers monthly, annual, and seasonal data at https://www.weather.gov/media/lwx/climate/ dcatemps.pdf. A review of the annual data shows that Washington’s seasonal temperatures had not been significantly different than prior years or the norm. For those who live here, the finding may be a surprise as it seemed to be a more mild winter in 2021. However, when the snow fall data is reviewed, the trend is different. Many news articles can be found on the internet focusing on how little snow precipitated in the 2021 season, and the general trend of less snowfall over the past few years. Indeed, the lack of snowfall in the 2021 winter was quite noticeable and extraordinary for local residents. I did not have to check the records on this to validate the observation, but I did so anyway. The Washington Post edition of 1/14/2021 reported that as of 1/14/2021, it had been 694 days in a row without at least a half inch of snow in Washington (and the season was still ongoing). This is a record. Apart from the next highest records in 1999 and 1973 at 693 and 617 days respectively, the next 7 longest streaks varied from 428 to 357 days. The Washington DC snowfall norm is 13.7 inches for the season. The 2020-2021 (Jul-Jun) was only 5.4 inches. The data may be reviewed at https://www.weather.gov/media/lwx/climate/dcasnow.pdf.

Hungry Bluebird mouths wide open at box 3. Photo: Cindy Morrow, 6/21/21

A robust bird population will be dependent on an abundant food supply. Food supply too can be correlated to adequate rainfall and soil fertility. While there were no negative determinants on the food supply in 2021, there was a bounty with the 17 year cicada life cycle emergence, en masse, of the cicadas. Consequently, birds had a new and plentiful food source in the environment. Growth rates of the nestlings were healthy and many of the nest boxes were used twice.

Conclusions

The Virginia Bluebird Society’s Langley Fork Park Bluebird Trail had a successful season in 2021, in great part due to a mild winter, active management, and a once in 17 year cicada ample food source. A total of 63 birds (33 Tree Swallows, 26 Bluebirds and 4 House Wrens) fledged at Langley Fork Park Bluebird trail.

References

· Stanford Report, January 10, 2005, Bird populations face steep decline in coming decades, study says. Mark Shwartz

· Population limitation in birds: the last 100 years. Ian Newton

· 17-year Cicadas: Bird Buffet or Big Disturbance? May. 18, 2021. Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. https://

nationalzoo.si.edu/migratory-birds/news/17-year-cicadas-bird-buffet-or-big-disturbance

· D.C.’s lack of snow over the past two winters is making history. Capital Weather Gang. https://

www.washingtonpost.com/weather/2021/01/14/washington-dc-snow-drought/

She reported that the Country Club Hills community hosted the Friends of Accotink Creek and were joined by special guest Delegate David Bulova – a true champion of the environment – for their annual ‘Creek Cleanup at The Commons’.

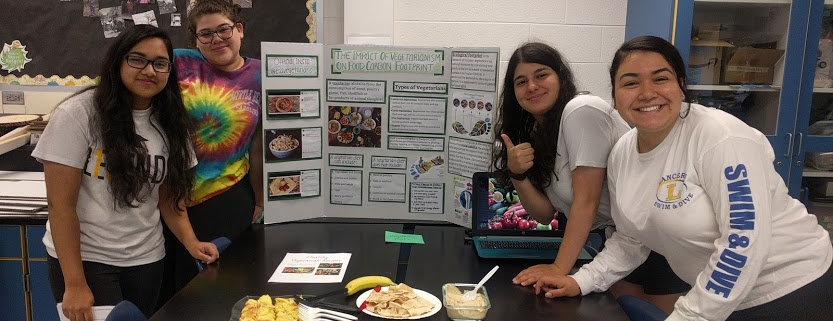

She reported that the Country Club Hills community hosted the Friends of Accotink Creek and were joined by special guest Delegate David Bulova – a true champion of the environment – for their annual ‘Creek Cleanup at The Commons’. Another afternoon highlight for the kids and adults alike was catching and counting the various macro-invertebrates in the water. This is a good Stream Monitoring technique because benthic macro-invertebrates are affected by physical, chemical, and biological

Another afternoon highlight for the kids and adults alike was catching and counting the various macro-invertebrates in the water. This is a good Stream Monitoring technique because benthic macro-invertebrates are affected by physical, chemical, and biological  stream conditions. The macro-invertebrate evaluation scored this section of the stream as a 5 on a scale of 1-10 (Macro-invertebrate Community Index – MCI). A midrange MCI score alerts the team that work needs to be done to improve the stream’s health. Creating awareness is the first step towards recovery.

stream conditions. The macro-invertebrate evaluation scored this section of the stream as a 5 on a scale of 1-10 (Macro-invertebrate Community Index – MCI). A midrange MCI score alerts the team that work needs to be done to improve the stream’s health. Creating awareness is the first step towards recovery.