Reviewed by Michael Reinemer

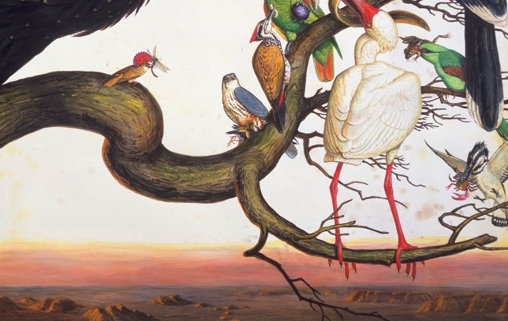

In the midst of an accelerating mass extinction where we are losing species much faster than science can identify them, this is an engrossing look at taxonomy, or how we organize life on earth.

Yoon laments our disconnects from nature. A child living among the Indigenous Tzeltal Maya people in Mexico can identify about 100 different plant species, Yoon says. How many American adults can do that?

She provides an account of “folk” taxonomies that are binominal, two-word descriptors the predate Carl Linnaeus, the botanical whiz kid from Sweden who published Systema Naturae in 1735. That system laid out the framework that most of us learned, the Linnaean hierarchy — kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, species. (Of course, we use that every time we select an unadulterated native plant for our garden, relying on the scientific name — genus and species — rather than a vague or even misleading common or commercial name. Don’t we?)

Later schools of thought refined how we might arrange living things. Well into the 20th century, “cladists” organized the tree of life around the branches (clades) based on evolutionary relationships. They famously declared that, technically, fish don’t exist. Lungfish, they would explain, are more closely related to cows than they are to salmon. That news would have been nonsensical to Linnaeus, and perhaps blasphemous to Izaak Walton. Walton described his 17th century meditation on conservation, The Compleat Angler, as a “Discourse of Fish and Fishing.” In any case, the cladists’ fish-dissing were fightin’ words to other taxonomists. With breezy, engaging insights, Yoon chronicles the debates.

Want to review a resource? We’d love to hear from you. Instructions for submission await your click and commitment.