Responding to Misbehavior in Nature

Photo: FMN Janet Quinn

Article by FMN Laura Handley

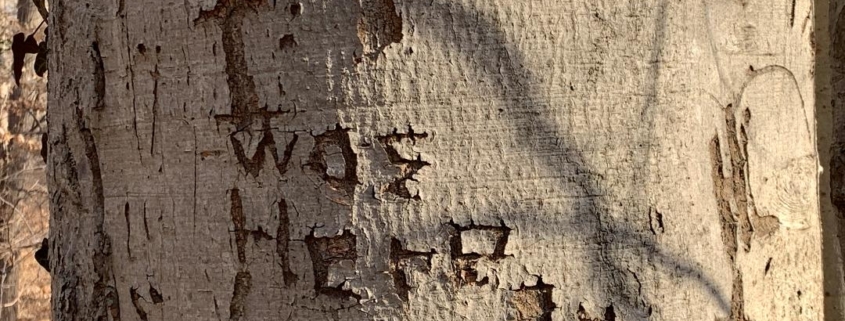

With all the time we Master Naturalists spend in nature, most of us have witnessed some sketchy behavior out there. Perhaps you’ve seen a lady digging trillium from the forest floor, or kids pulling the wings off insects, or young lovers carving their initials into the smooth bark of a beech tree. What are we to do in such a situation? Do we cringe and walk on, averting our eyes from the misbehavior? Are we obligated to jump in and put a stop to it?

Thankfully, not the latter. As Master Naturalists, we have no duty to act when we see someone messing with nature. We also have no enforcement authority, so we’d have no more standing than any other passersby to tell someone to stop what they’re doing. And unlike park rangers, we’re not trained to enforce park regulations. Our training includes many best practices for observing nature and moving through natural areas, but it doesn’t cover the rules that apply in any particular area. Rules can differ quite a bit from one park system to another: an activity that’s banned in one place might be perfectly fine elsewhere. (For instance, the Fairfax County Park Authority is adamantly against foraging for edible plants, but Sky Meadows State Park in Fauquier County allows visitors to gather small amounts to be consumed within the park, and some national forests even allow commercial harvesting with the right permit.)

What we are trained to do is understand nature and share our knowledge with others. And most misbehavior toward nature is rooted in a lack of either knowledge or empathy (which often arises from knowledge). It’s safe to assume that if someone makes the effort to visit a natural area, they value nature and wouldn’t want to ruin it; they often just don’t know that what they’re doing is bad, or bad enough to make a difference. And so our best response, when we see someone doing something that looks harmful, is to start a conversation and see if we can advise them better. (Of course, we should always be careful when approaching strangers; some people can get belligerent when questioned. Use your best judgment, and remember that it’s not worth risking your safety to intervene.)

A good way to start the conversation is with a friendly, open-ended question: “What are you doing there?” Give the person a chance to explain what they’re up to. It could be that you caught them at the worst-looking moment of something innocuous, such as trampling vegetation while trying to retrieve a lost ball. It could be that they don’t know they’re doing harm, such as by walking off-trail or collecting wild seeds indiscriminately without a plan to ensure those seeds germinate and thrive. It could even be that they think they’re helping when they’re actually doing harm, such as by killing bugs that pose no threat or cutting down native vines from trees. Or–ideally–it could be that they know exactly what they’re doing and are going about it in a legal and environmentally responsible way, such as foraging the berries of an invasive plant to keep that plant from spreading, or collecting a small sample of a local ecotype of a native plant to add to their garden in place of a nursery-grown strain from out of state. (I hope this last option becomes more common as people become more aware of ecological issues and the many productive interactions we can have with our local ecosystems!)

Once you’ve established a rapport with the person, and once you’ve learned what their goals are, you can help them find a more ecologically sound way to meet those goals. If those kids are feeling bored and destructive, you could steer them away from the poor innocent bugs and toward an invasive plant that needs removal. The trillium-gathering lady might not know that most woodland wildflowers require the soil chemistry and mycorrhizal symbionts of the forest floor; once she learns those plants will almost certainly die if transplanted elsewhere, she’d probably take your suggestion to leave them be and look instead for native plants that would thrive in a garden (especially if you point her toward resources and retailers like Plant NoVA Natives and Earth Sangha). And if the lovers want to memorialize their relationship, instead of scarring an older tree, why not plant a young one that can grow along with their love? In an ideal situation, everyone can leave satisfied; if not, at least the culprit will know better and you’ll have done all you can to share your knowledge and encourage better stewardship.

While you’re talking, I wouldn’t brandish the Master Naturalist credential to convey authority, but it’s not a bad idea to mention the program or the resources on our website, especially if the person seems interested in learning more. Who knows–maybe you’ve found a new applicant for the next Basic Training!