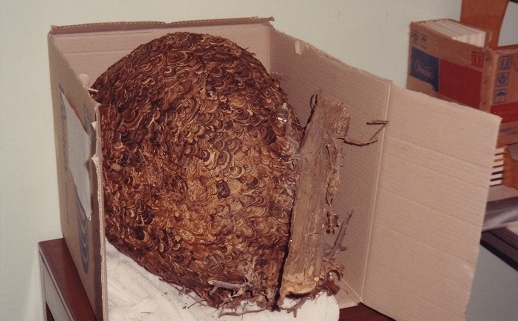

Feature photo: At the Buildings and Grounds Office, Camp Zama, Japan. The size of the hornet’s nest is placed in context with the office surroundings.

Photos and article by FMN Stephen Tzikas

Every now and then I see a wasp building a mud-based tubular shaped nest in some corner of my home’s front door portico. These are mud dauber wasps. Mud wasps are solitary wasps, which means it builds a single nest for itself. They are fairly common and the internet has photographs of their nests. That got me thinking about the most magnificent insect nest I’ve seen.

While serving as the Chief, Environmental Management Office for the US Army in Japan, I had many partners and stakeholder on the installations. One of them,

Close-up of the hornet’s nest from Camp Zama, Japan

in the same Directorate of Engineering and Housing as my office, was Buildings and Grounds. In the pre-internet age, we visited other offices in person to conduct business, and the live interaction was always valuable and rewarding. During one visit to the Buildings and Grounds Office on February 10, 1993, some of its employees came back with a nice catch from someplace on the installation. It was the largest hornet’s nest I ever saw. I didn’t know it at the time, but years later after I took the photographs, I would be in a much better position to appreciate them as a Master Naturalist.

Close-up of the intricate and beautifully scalloped pattern of the Camp Zama, Japan, hornet’s nest

Hornets are a type of wasp, though wasps typically are paper wasps and yellow jackets. There are differences in the way the insects build their nests. Hornets construct nests using chewed wood and saliva and can take months to build, giving it a papery look. Hornet nests are also much larger than wasps nests, being larger than a basketball size. If you ever encounter such a nest, be careful. Hornets can sting repeatedly, and may cause allergic reactions that can be life threatening. If you discovered such a nest on your property, it may be wise to have a professional exterminator address the problem. Hornet nests are structured in a closed architecture, that is, the nest has a surrounding envelope, with a small opening at the bottom of the nest.

Paper wasps also create nests out of a paper-like product of maceration. Paper wasps nests may have an exterior that looks less elegant, a sort of conglomeration of parts and crater-like surfaces often lacking an envelope. A yellowjacket wasp nest will have a single opening, but these wasp nests are usually in the ground, and only visible as a small hole in the dirt.

Upon returning to the US in 1994, I worked at the Washington Navy Yard for a couple years. One of Naval installations under our responsibility was the Patuxent River Naval Air Station in Maryland. At least on one occasion if not more, I drove out to the location for an environmental evaluation. Runner up to the Camp Zama, Japan, hornet’s nest were the termite mound nests at this Maryland location. I recall they looked nearly as high as humans, but in some parts of the world they can be 25+ feet. Besides those tall termite mounds, I saw many wild turkeys and large bulb eye insects nearly a couple inches in length. I was beginning to think about what an unusual place this Patuxent River area was.