Photo: Plant NoVa Natives

Article by Elaine Kolish, Vice Chair, Fairfax County Tree Commission, Certified Master Naturalist

English Ivy is everywhere, in our neighborhoods, along our roads, and in our parks. It climbs over fences, covers sheds, and carpets forest floors. Unfortunately, many people think English Ivy is a benign plant that grows in the shade, where nothing else grows.

The truth is English Ivy is harmful in many ways. Even if well-manicured and contained on the ground, English Ivy provides a resting spot for mosquitos on hot days or hides puddles where they can breed, and who wants that! More importantly, when it covers forest floors it displaces native plants, and eliminates needed and productive biodiversity. When it climbs trees it harms and eventually kills them, which eliminates the important environmental benefits trees provide, such as wildlife habitat, preventing stormwater from entering streams, cooling our environment, and combatting climate change.

Trees are one of our best tools for capturing carbon dioxide, which is necessary to fight global warming. According to the US Forest Service, America’s forests sequester about 16% of the annual emissions from the United States. Because trees are such excellent carbon sinks, there are large scale reforestation efforts underway. President Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Plan calls for more than one billion new trees to be planted over the next 10 years. In addition, the government’s experts know that controlling invasive species that kill trees is an important strategy for enhancing carbon capture.

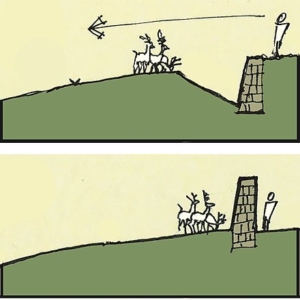

We as individuals also have an important role to play in controlling English Ivy at home and in our natural areas. Otherwise it covers everything in its path, and when left unchecked, English Ivy grows vertically (by rootlets on the stem). On trees, the weight of the vine weakens and breaks limbs, which can make trees more susceptible to infections, and over time the vines cover trees so totally that they die. But that’s not all. When English Ivy goes vertical it matures. It then will flower and set fruit. Birds then eat and disperse the fruit, spreading the English Ivy invasion.

Homeowners can protect their costly landscaping and help the environment by eliminating English Ivy from their gardens or, at a minimum, by keeping it from growing up trees. Wearing gloves, cut all the vines on a tree about two feet up and again at ground level. There is no need to pull the vines off the tree. Deprived of water and nutrients from the soil, the vines will wither. You will have to repeat this occasionally if you do not remove all the ivy. Hand pulling after a rain softens the soil is the best way to get rid of English Ivy. The debris should go in the trash. Do not compost it or put it out with the brush collection as it will continue to grow and spread in these locations.

The good news is that there are lots of alternative native ground covers that will support pollinators and our environment. You can find excellent suggestions in the Native Plants for Northern Virginia guide, such as Virginia Creeper and ferns.

You also can help our neighborhoods, forests, and parks by becoming a Tree Rescuer, or by working with organizations that do invasive management including pulling ivy. Working together, we can ensure the health of our wonderful trees and improve our environment, as well as our personal well-being, by spending time in nature.