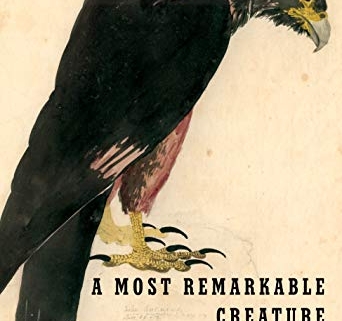

Review of A Most Remarkable Creature, by Jonathan Meiburg

Review by FMN David Gorsline

Musician, traveler, and nature writer Jonathan Meiburg begins his book with a mystery: who — or what — killed bird G7? Eventually, he answers that question. Along the way, into his story of caracaras living and extinct, he packs 16 pages of excellent color photographs, a magpie’s collection of 50 pages of end notes, and a challenging trip up Guyana’s Rewa River.

We naturalists of the mid-Atlantic rarely encounter caracaras on our home turf. Only one species of these birds of prey, Crested Caracara (Caracara plancus), has a range that extends into Texas and Florida (older authorities recognize this population as C. cheriway). But the group is extensively represented in South America by five genera, occupying a variety of habitats. Meiburg describes the general body plan as “ten separate attempts to build a crow on a falcon chassis, with results falling somewhere between elegant, menacing, and whimsical” (p. 9); caracaras share with (not closely related) corvids intelligence and curiosity. In short, an engaging subject for Meiburg’s equally engaging book.

The book’s coverage of these ten species is a bit uneven, with emphasis on the wild birds found where Meiburg was able to travel. Readers might regret the material devoted to captive birds in aviaries in the United Kingdom, but with a bird so adaptable to living with humans, perhaps these are pages well spent.

The book’s strengths are that trip up the piranha-laden Rewa to see “bush auntie-man” (Red-throated Caracara, Ibycter americanus), involving a waterfall portage, columns of army ants, and crab-sized Theraphosa spiders; a visit to minor islands of the Falklands archipelago to find “Johnny rook” G7’s killer; and Meiburg’s introduction of 19th-century Anglo-Argentine naturalist William Henry Hudson. Hudson was closely observant, and more than a bit romantic.

Depending on your taste, your reaction to Meiburg’s anthropomorphizing may vary; it’s mostly endearing, and maybe unavoidable when a Black Caracara (Daptrius ater) peers at you with affable opportunism.

—

A Most Remarkable Creature: The Hidden Life and Epic Journey of the World’s Smartest Birds of Prey, by Jonathan Meiburg, Knopf, New York, 2021, 336 pages