The Andromeda Galaxy with a Pair of Binoculars

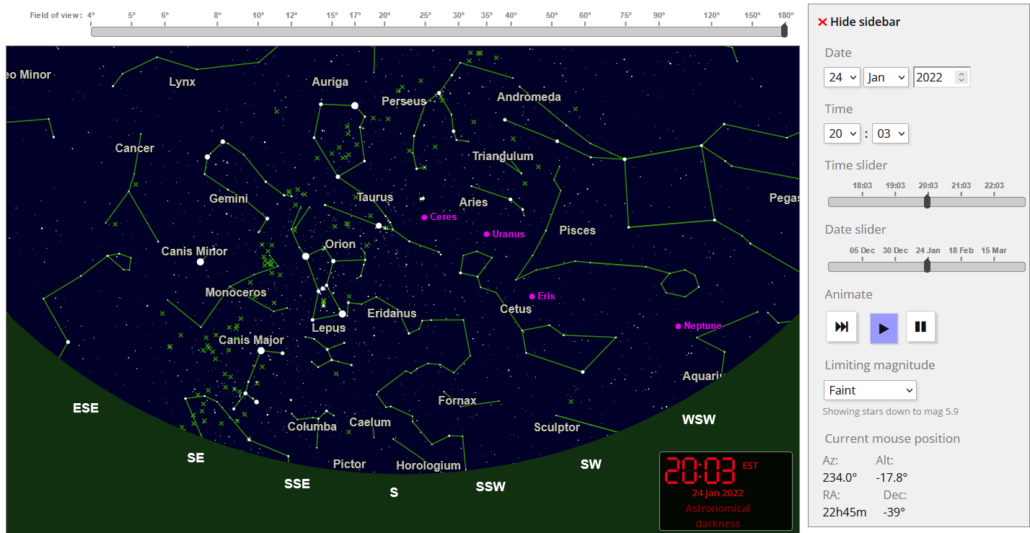

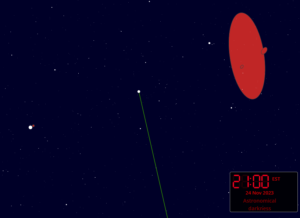

Feature illustration: The Andromeda Galaxy Sky Area. Excerpted from https://in-the-sky.org/skymap.php. The excerpt is set to November 24, 2023 at 9:00 PM from Reston, VA, but any time and location may be selected. Notice the Great Square of Pegasus and the red oval above it.

Article by and illustrations courtesy of FMN Stephen Tzikas

The Andromeda Galaxy is an object often mentioned in sci-fi films and

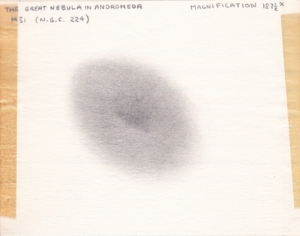

Illustration by author: 1979 sketch of Andromeda Galaxy, using a 60mm Selsi refractor telescope and 187.5 magnification.

literary works. It is our closest galaxy (not including Milky Way satellite galaxies) and can be seen by the naked eye in a dark sky location. I was thrilled to see it through my childhood telescope. With binoculars it is a fuzzy patch-like object. That little patch is just the central core or brightest part of the galaxy. The rest of the galaxy is so dim because of its 2.5 million light year distance. If we could brighten the galaxy, it would be four full Moon lengths across the sky. The central core of the Andromeda Galaxy with a pair of binoculars looks very similar to my 1979 illustration of it through a Selsi 60mm telescope. The area around the Andromeda Galaxy is also home to other surprises too.

Close-up of the Andromeda Galaxy Sky Area. Nu-And (magnitude 4.5) is the bright star to the upper left of the Andromeda Galaxy outline. The diagram’s center bright star, with green constellation line underneath, is Mu-And (magnitude 3.9). The bright star in the center-left is Mirach (magnitude 2.1) with NGC 404 (red dot) next to it. This illustration is also excerpted from https://in-the-sky.org/skymap.php for Nov. 24, 2023 at 9:00 PM.

A pair of binoculars can see EG Andromedae (EG And), a variable star. You can take measurements of it brightening and dimming via a visual comparison to nearby stars that are fixed in brightness. You can obtain a detailed star chart for measuring magnitude changes through the Variable Star Plotter at the AAVSO website and then inputting EG And. You can submit your measurements to their database. See https://app.aavso.org/vsp/

With a small telescope a little larger than binoculars, two more interesting objects can be seen nearby. One is a beautiful

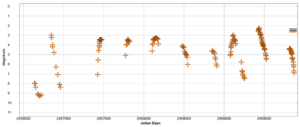

Excerpted from http://informationaboutstars.com/starinfo.dc/star/id-36618/. The website is from “about the stars Planetarium” on HIP 3495, a.k.a. EG Andromedae in the constellation Andromeda. The star varies in magnitude from 6.97 to 7.8, and is circled adjacent to the Andromeda Galaxy. In another blue circle, Nu And is to the upper left of EG And.

double star named gamma Andromedae, or Almach. Through the telescope it appears as a bright, golden-yellow star next to a dimmer blue star. Some observers may get the impression that the blue star has a green hue. This green hue is an optical illusion caused by the contrast of the colors on the eyes and is very rare to see. In actuality, there are no green stars, because any star emitting radiation in the green spectrum is also emitting enough red and blue radiation to combine and form white light. This double star, along with the double star named Albireo in the constellation Cygnus, are often described as the most visually colorful double stars in the sky.

The other nearby interesting object is beta Andromedae, or Mirach. It is a prominent orange/red hue star northeast of the Great Square of Pegasus. The galaxy NGC 404, also known as Mirach’s Ghost, is seven arcminutes away from Mirach. In a small telescope, it appears as a fuzzy star. NGC 404 is located about 10 million light years away, or about 4 times Andromeda Galaxy’s distance. Though NGC 404 is not as large or bright as the Andromeda Galaxy, is still worth a look. It is easy to find, and a one of the brighter magnitude galaxies to observe in the sky.