“Distillation” on the Trail

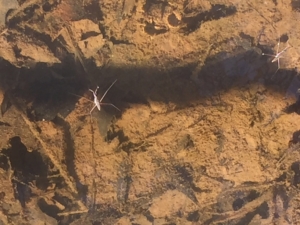

Charcoal Trail Greenstone Outcrop at Catoctin Mountain Park

Article, photos & illustration by FMN Stephen Tzikas

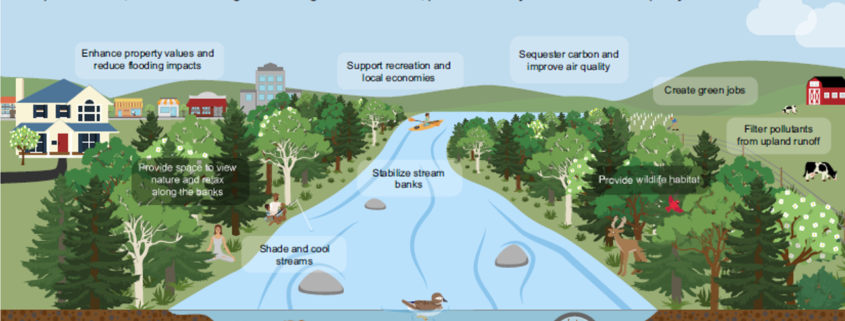

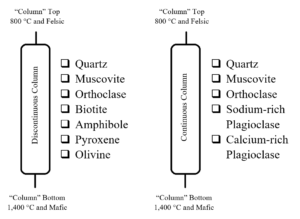

A few months ago, I prepared a roadside chemical engineering field trip to the Catoctin Iron Furnace in Maryland, for the local chapter of the American Institute of Chemical Engineers. One of the features on that excursion was a discussion of nature’s “distillation column.” While chemical engineers study distillation at university, nature has its own type of “distillation column.”

The Bowen Reaction Series

Geologists call it the Bowen Reaction Series. The Bowen Reaction Series is a set of reactions that occur when molten igneous rock cools, usually on its way to the surface. These reactions can be rather gradual (“continuous”) or abrupt (“discontinuous”). Virginia has many igneous rocks, often delivered to the surface as a consequence of past orogenies, or mountain building collisions with land masses off the East Coast, over the period of the last billion years. Locally, one can find igneous rocks at Great Falls Park and its museum, as well as the outside massive rock collection surrounding the property of USGS in Reston.

A little further west and north of Fairfax County is mountainous terrain. One finds a lot of greenstone, such as the old greenstone lava flows of Shenandoah National Park, or those rocks of Catoctin Mountain Park. Greenstone, a term for dark green metamorphic rocks, is primarily composed of altered mafic igneous rocks like basalt and gabbro. These basalt and gabbro rock textures would likely have olivine, pyroxene, and calcium plagioclase in them. When these rocks underwent metamorphism, secondary minerals formed like chlorite, actinolite, and epidote, contributing to the green color. Specifically, about 500 million years ago molten lava rose up through fissures on the Earth’s surface creating the igneous rocks like basalt. Through metamorphic processes that occurred afterwards, this rock was transformed into metabasalt greenstone. Hence, the greenstone you will see all around at nearby Catoctin Mountain Park is a result of “natural distillation” processes initially originating from the Bowen Reaction Series.

Charcoal Trail Greenstone Rock Samples at Catoctin Mountain Park

Felsic and mafic rocks are two main types of igneous rocks. Basalt and gabbro rocks are known as mafic rocks. A mafic mineral or rock is a silicate mineral or igneous rock rich in magnesium and iron. Most mafic minerals are dark in color, and common rock-forming mafic minerals include olivine, pyroxene, amphibole, and biotite. Mafic rocks often also contain calcium-rich varieties of plagioclase feldspar. Basalt is an extrusive rock, while gabbro is intrusive. Extrusive rock refers to the mode of igneous volcanic rock formation in which hot magma from inside the Earth flows out onto the surface as lava or explodes violently into the atmosphere to fall back as pyroclastics. In contrast, intrusive rock refers to rocks formed by magma which cools below the surface.

At the other end of nature’s “distillation column,” we find felsic rocks, such as granite, that are high in light-colored minerals, including feldspar and quartz. They are high in silica (SiO2), while mafic rocks are low in silica. Felsic rocks are also enriched in the lighter elements such as silicon, oxygen, aluminum, sodium, and potassium.