Porch Sitting

By Jerry Nissley

Porch sitting – A function exclusively characterized by occupying space on a porch in a seat, hence the name. The porch can be a deck, patio, or similar structure but must include a chair or a bench so one can sit. What one does while porch sitting is up to the individual. Recently I’ve seen friends and neighbors getting together for dinner or libations by ‘porch sitting’ while maintaining appropriate distancing.

I use my porch and deck primarily to observe activity in my backyard while enjoying a good cup of coffee. You know, to keep an eye on those rascally birds, squirrels, skinks, bugs and occasional fox that flit, flutter and fly around throughout the day.

As it happened one day last week while I was porch sitting, I observed a blue jay purposefully shuttling back and forth from a copse of trees into a row of massive photinia that line a portion of my back-neighbor’s yard. I figured it was busy catching insects to feed chicks in a nest buried deep within the photinia. A vibrant blue dart trimmed in bright white swooping 25 feet between perches, very eye-catching. As the light of day began to fade, I noticed its brilliant blue coloration fading as well. As the direct sunlight faded the jay appeared to turn a grey-brown. The bright white outline of primary tail and wing feathers was basically all I continued to see as dusk settled in.

I recalled then a science project my daughter did in high school on iridescence, pigment, and color. She used a blue jay feather as an example of pigment and light reflection. That project was more than a few years ago, so I decided to do additional research to refresh my memory on the subject. Research on why a blue jay appears blue has been refined quite a bit since that science fair project so, at risk of telling a group of Master Naturalists something they already know, I thought I would share my findings.

This article is not intended to fully describe a blue jay to you but stirring your mind by way of a sincere reminder is always appropriate for an FMN article. Briefly, according to Cornell Lab Bird Academy the blue jay (Cyanocitta cristata) is a passerine bird in the family Corvidae, native to North America. It resides throughout most of eastern and central United States and breeds in both deciduous and coniferous forests so it is common in residential areas such as our local backyards.

Color is a theme for this article so its worth highlighting that a blue jay’s plumage appears blue in the crest, back, wings, and tail, and its face is white. The wing primaries and tail are strongly barred with black, sky-blue and white. However, the intense blue we perceive on a blue jay is due to the microscopic structure of its feathers and the way they reflect blue and violet light. This is known as structural coloration.

A simple way to experience structural coloration is to hold a blue feather up to the sky so it is back-lit. With sunlight streaming through the feather the blue color vanishes and the feather appears a drab grey-brown. However, bring the feather down so the light bounces off, scattering blue wavelengths of light and the feather appears blue once again. Indeed, for many years scientists thought birds look blue for the same reason the sky does: red and yellow wavelengths pass through the atmosphere, but shorter blue wavelengths bounce off gas molecules and scatter, emitting a blue glow in every direction. But more recently Richard Prum, an ornithologist at Yale University, discovered that the blue in bird’s feathers is slightly different.

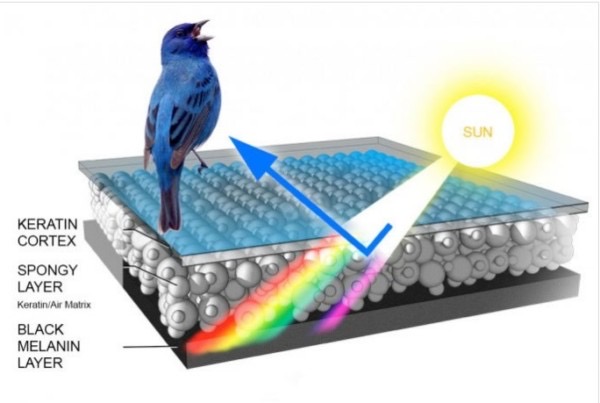

Prum discovered that as a blue feather grows, protein molecules called keratin (located within the feather cells) separate from water molecules, like oil from vinegar. When the cells die, the water evaporates and is replaced by air, leaving a specific structure of keratin interspersed with air pockets. This three-dimensional arrangement of the keratin/air layers within feather barbs is what reflects blue wavelengths of light back to our eyes as illustrated in Cornell’s graphic below. Prum also discovered that different shapes and sizes of these keratin/air layers create different shades of blue that we see among various species of birds. However, even though the appearance of blue is a structural color Prum determined the key to this entire phenomenon is the presence of the pigment melanin, because without it all blue birds would look white.

Visible light strikes the feathers and encounters the keratin-air nano-structures. The size of the nano-structure matches that of the wavelength of blue light. So, while all of the other colors pass through the feather, the blue does not. It is reflected, so we see blue. As further evidence, if the ‘blue’ feathers of a bird are ground up they turn brown. Once the nano-structures are destroyed, you see the bird’s true color.

You can explore the uniqueness of blue feathers by observing a feather in different light conditions. In the shade, a blue jay’s feather will appear gray because the intrinsic gray-brown color of the melanin pigments is visible. Looking through the feather into the light, you’ll see just the gray-brown color of melanin as light passes through the feather. When you place it so that light falls directly upon it and is reflected to your eye, the feather will appear blue. Try the same with a cardinal’s feather and it will appear red each time.

The blue jay is a noisy, bold, and aggressive bird. It is a moderately slow flier and thus it makes easy prey for hawks and owls when flying in open areas. Virtually all the raptorial birds sympatric in distribution with the blue jay may prey upon it, especially swift bird-hunting specialists such as the Cooper’s, red-tailed and red-shouldered hawks common in our Northern Virginia area.

Jays may occasionally impersonate the calls of raptors, possibly to test if a hawk is in the vicinity, though also possibly to scare off other birds that may compete for a food source. Because flight speed is somewhat slow it may impersonate hawks as passive defense mechanism. I mention this factoid because of another observation I made while porch sitting. I noticed a resident Red-tailed hawk circling a tall oak in the yard making its unmistakable high-pitched hawk shriek and what I thought to be its mate responded from a perch in the tree. I thought its mate was simply calling back but as the in-flight hawk approached the tree a blue jay fell out of the tree in a directed free-fall from the perch into low, dense bush cover.

Research into the phenomenon of mimicry revealed blue jays are able to make a large variety of sounds and individuals birds may vary perceptibly in their calling style. Like other, corvids (crows, magpies, ravens, etc) they may even learn to mimic human speech. Their most commonly recognized sound is the alarm call – a loud, almost gull-like scream. There is also a high-pitched jayer-jayer call that increases in speed as the bird becomes more agitated. I have seen backyard blue jays use this call to band together to mob potential predators such as crows and drive them away from the jays’ nests.

OK, so that’s my story and I’m sticking to it – back to my porch I go. As Satchel Paige (or A.A. Milne, et al.) once said, “Sometimes I sit and think and other times I just sit.”