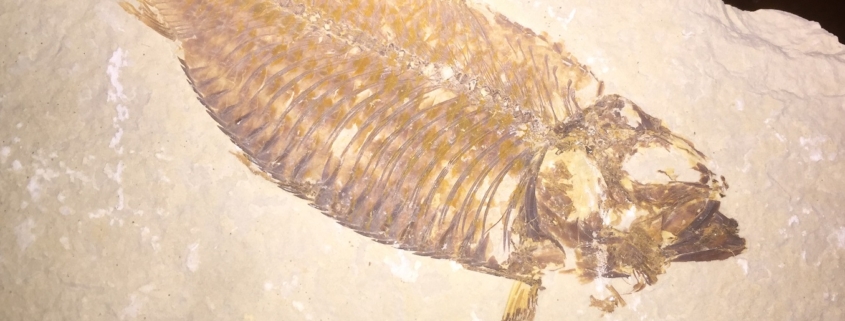

Feature photo: Fish Fossil, Green River Formation, Western United States.

Article and photos by FMN Stephen Tzikas

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard

Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on;

Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear’d,

Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone

So goes the second stanza of John Keats’ “Ode on a Grecian Urn” that I vividly remember from my High School days. These were the same words that flashed in my mind upon viewing a fish fossil my friend gave me a few months ago. Funny thing it is, how the poet sometimes seems to precede the scientist in me.

The famous English poet’s ode appreciates the timeless art on an urn, and so too, the fish fossil in my mind was a presentation of beauty and immortality, having patiently waited millennia to tell its story. And just as in the original poem, we have the conclusion of the poem which can equality apply to the fish fossil:

When old age shall this generation waste,

Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe

Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say’st,

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty,”—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

While these herring fish fossils have their origin in the limestone of the Green River Formation, residents of Fairfax County do not need to go that far, or even leave the county, to find fossils.

My exposure to fossils began as a child reading the How and Why Wonder Book of Dinosaurs, which indicated that the first, near complete, skeleton of a dinosaur was discovered in Haddonfield, NJ. Since that was in my home state, I hoped to visit the town one day. Eventually I would indeed visit that town to see the Hadrosaurus statue commemorating the find in 1858 that started the field of dinosaur paleontology.

During the Triassic Period (201 – 252 Mya), dinosaurs left behind both bones and footprints in Virginia. Fish from local lakes were preserved during the Jurassic (145 – 201 Mya). In the 1920s, dinosaur tracks were discovered at nearby Oak Hill. The Northern Virginia Community College (NVCC) offers many one-day one-credit geology excursions in our general area. I completed many of these courses and had the opportunity to see fossils during these excursions.

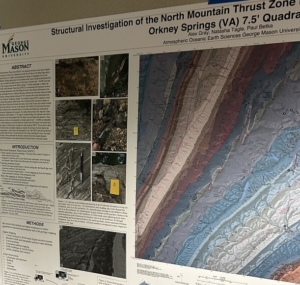

On June 24, 2017, I attended the geological field study trip for the

Oak Hill Dinosaur Skin Print, June 24, 2017, 1.5 by 2 Foot Scale

Triassic-Jurassic Rifting of North America in the Triassic Lowlands of Northern Virginia. One of the sites on that trip was the Oak Hill Estate (Home of President James Monroe). This site contains dinosaur tracks. The rock type here is the Lower Jurassic Turkey Run Formation (197 Mya). The fossils are of Eubrontes foot tracks and a rare skin print (see my photograph). Also fossilized was a lungfish burrow from the Jurassic, which had estivated to survive through the summer. Ripples, raindrops imprints, and bioturbation were evident in fossils we saw.

Photo:Holmes Run Gorge Fossils, Nov 18, 2017. Shown here are fossils (Skolithos Linearis) in well-cemented quartzite of the early Antietam Formation. These are Virginia’s oldest fossils and date to the Cambrian Period (485 – 539 Mya).

On November 18, 2017, I took another NVCC geology excursion for the Geologic History of Holmes Run Gorge at the Dora Kelley Nature Park in Alexandria. At the main gorge area we discussed the quartz rocks. Quartz is the last mineral in the Bowen reaction series of fractional crystallization.

I find the Bowen reaction series fascinating as it has some correlation to fractional distillation in my field of chemical engineering. I collected a sample of cloudy white milky quartz, which is extremely resistant to weathering. The cloudiness of milky quartz comes from microscopic inclusions of fluids that have been encased in the crystal from the time the crystal first grew. Our professor showed multiple examples of Quartzite with slashes (see my photograph). High-energy waters transported these cobblestone size rocks originating from the Harper’s Ferry Antietam Formation. The formation was largely quartz sandstone with some quartzite and quartz schist. This formation underwent metamorphic changes. This Quartzite is a hard, non-foliated metamorphic rock that was originally pure quartz sandstone. The sandstone was converted into quartzite through heating and pressure usually related to tectonic compression within orogenic belts. Most noteworthy were the tubeworm line burrows, about a half billion years old. Samples were numerous.