The National Academies of Sciences, Medicine, and Engineering performed a study on Grand Challenges for Environmental Engineering in the 21st Century, which they published in 2018. It is now available to the general public and is a good, bracing read. The excerpt below is from the introduction. Yup, it’s 125 pages and will take longer than 15 minutes to absorb, but it’s worth the time. You can download the report and slides, too.

“The report identifies five pressing challenges for the 21st century that environmental engineers are uniquely poised to help advance:

1: Sustainably supply food, water, and energy

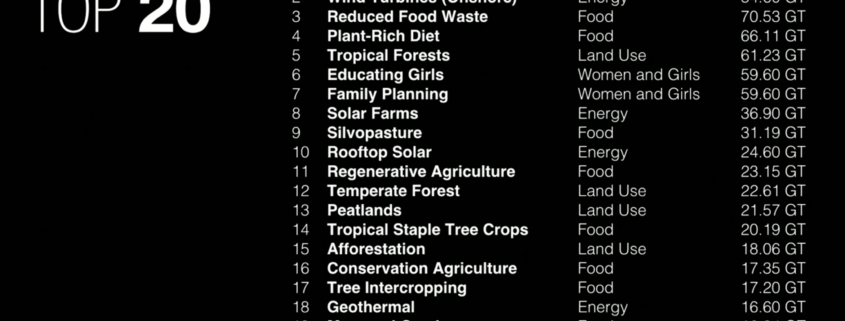

2: Curb climate change and adapt to its impacts

3: Design a future without pollution and waste

4: Create efficient, healthy, resilient cities

5: Foster informed decisions and actions

These grand challenges stem from a vision of a future world where humans and ecosystems thrive together. Although this is unquestionably an ambitious vision, it is feasible—and imperative—to achieve significant steps toward these challenges in both the near and long term.

The challenges provide focal points for evolving environmental engineering education, research, and practice toward increased contributions and a greater impact. Implementing this new model will require modifications in the educational curriculum and creative approaches to foster interdisciplinary research on complex social and environmental problems. It will also require broader coalitions of scholars and practitioners from different disciplines and backgrounds, as well as true partnerships with communities and stakeholders. Greater collaboration with economists, policy scholars, and businesses and entrepreneurs is needed to understand and manage issues that cut across sectors. Finally, this work must be carried out with a keen awareness of the needs of people who have historically been excluded from environmental decision making, such as those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged, members of underrepresented groups, or those otherwise marginalized.”