Some natural observations and a shout-out to the work of master naturalists

Article by Lisa Bright, Co-founder and Executive Director of Earth Sangha

In my line of work, I engage in extensive, if casual, surveying of native flora in the wild areas of Northern Virginia. For nearly twenty years, I’ve made it my job checking on the general conditions of our region’s wild areas, or rather the remnants of once wild areas, in every season. Mind you, my kind of survey is a non-scientific activity. Just a visual survey with the understanding of a hobby-naturalist.

Yet, you get to learn a lot from this repeated observations over the same areas. I take the trouble visiting all the nooks and crannies of our public and non-public lands where native plants are growing. And repeatedly over the years. I’ve noticed how the topography change over time and how plants interact with both natural and artificial physical changes. The overall picture I’ve gotten from my observations is not that pretty. Here is one fact that I cannot ignore: In our increasingly urbanized and suburbanized region, driven largely by human convenience and immediate economic returns, the native plants are the ones who are losing ground. Literally, that is.

I am sad to note that once common native plant species such as White Wood Aster (Eurybia divaricata) and Blue-stemmed Goldenrod (Solidago caesia) and Cornel-leaf Whitetop Aster (Doellingeria infirma), to just name a few, have become harder and harder to find in our woodlands. They are still there but not in any sizable quantities. They barely hang on. I name these species because of the simple fact that they are the foundation species in healthy woodlands and that they were once widely represented. Even ten short years ago, they were commonly found in any woodlands nearby. They are now in serious decline. Their habitats are degraded, and in many instances they lost outright the entire habitats by development. I’m not going to name other native plants who were once abundant but are now in decline.

This comes at a time when our wild areas and native flora are finally getting the recognition they deserve from the general public. There are growing number of people and organizations who band together to protect the wild habitats for native flora and fauna. I believe that if we work together, harder and smarter, we can reverse the trend. It’s not too late.

The habitats once lost are gone forever. You can’t recreate natural areas. If anyone claims that it can be done is either ignorant or plain kidding himself. Our hope then lies in rehabilitating the habitats in decline.

Then it is all the more useful to see how the natural habitats are being destroyed and what we could do about it. I’m no expert on this, but I think there are several immediate and specific issues that can be addressed:

1. An issue of poor management. The land owners, public or private, rely too much on the judgment or discretion of hired contractors who understand next to nothing about wild habitats or plants in general. They were told to go kill trees that might interfere with the power lines, and they damn kill everything in sight. Who could blame their diligence? I’ve witnessed countless times how these contractors steadily shrink the forest edges by chopping off indiscriminately any living woody plants. In their wake, a long line of dead Mountain Laurels (Kalmia latifolia) along the forest edges. These contractors desperately need the qualified and quantified instructions and tighter supervision by the land owners.

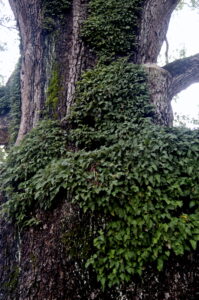

Take look at the two photos above. The plot is about 4 acres of narrow but long neighborhood woodlands (presumably belonged to a nearby HOA community) in Centerville. A contractor hired by either the VDOT or a power company chopped off trees on the edges of Rt. 29, and just dumped all the tree trunks and branches unceremoniously into the woodlands just across the trail and left. The contractors did this every time, and nobody raised an issue. It’s a forgotten place. The forest floor once featured one of the better habitats for White Wood Aster and Blue-stemmed Goldenrod in this acidic Oak-Hickory forest remnant. Now I cannot find a single Aster or Goldenrod. Those numerous Pinxter Bloom Azaleas along the edge were also long gone. In their place invasive Alianthus altissima (Tree of Heaven) and Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) have appeared. This is just one example which repeats itself everywhere. The feature photo heading this article shows what our woodland floor would look like when left alone. It’s taken from a nearby park.

2. An issue of excessive mowing and untimely mowing. When it comes to open meadow areas, mowing is a necessary tool for managing the habitat. The problem is that the heavy tractor mowers with low deck not just cut the plants but they cut into the ground, thereby making it easy for weedy invasive plants entering. I’ve noticed that the Manassas Battlefield National Park contractors do a far better job at just cutting the plants without necessarily disturbing the ground, compared to power line easement meadows. One reason is that at Manassas Battlefield the contractors are harvesting hays, and the best way to continue harvesting good-quality hays is not to disturb the ground. On the other hand, the main reason for mowing in the power line meadow is to destroy plants. That is one reason why the quality of flora is widely different from one power line easement to the next. And from one year to the next.

Still, the best native herbaceous vegetation in our region can be found under these power lines because we’ve essentially lost our edge-of-wood meadows to various human activities and development.

One of my pet peeves is mowing unnecessarily and at wrong time. It would be better if we let the plants complete its life cycle. If seeds are allowed to form and be dropped and eaten by animals, mowing can be a useful management tool.

3. Let’s limit the recreational use of wild habitats.It is hard to believe that at this critical juncture where the environmental degradation threatens the very systems on which our life is dependent, we regard public parks only as recreational resources. There are some parks that I no longer visit because there is nothing left to discover. These parks are known for deluxe parking lots and luxurious trails, after killing off a group of healthy and mature canopy trees. These parks have become a sad place botanically. Some smaller neighborly parks often suffer from excessive accommodation of exercise equipments. At one of our neighborly parks, a series of them are installed at every 50-feet intervals by well-intentioned but ill-informed Scouts or other volunteer groups. A whole lot of native shrubs and herbaceous plants had to be killed to give the rooms for these exercise equipments. Many Viburnum dentatum (Arrowwood Viburnum) and Deerberry (Vaccinium stamineum) were sacrificed for these installations. They are left unused anyway. If the mountain biker groups ask for building bike trails, we don’t have to give away the pristine section of forests where the Blueberry (Vaccinium pallidum) and Black Huckleberry (Gaylucassia bachata) have formed colonies over several centuries. I don’t think the bikers were asking for a pristine site!

It is high time we view our natural habitats as what they are. It’s a living organism who plays a critical role in the natural ecosystems. To simply put, we are facing an ecological crisis where a lack of healthy native plant communities creates all kinds of problems. Just look at all the damages from stormwater runoff. Only healthy forests could absorb, hold, filter, and regulate the rainfall and rain flow. We’ve effectively destroyed that natural system.

There aren’t enough forests in our region to handle all the water and air pollutions. Also our forests, our parklands, are not in the best form. They need a lot of attention, but our park systems don’t receive enough funding.

4. Controlling invasive plants and early detection of such invasion. Eradicating invasive plants may be impractical given the pervasiveness of the problem. But we can manage to control them by focusing on protecting the best areas first and increase the presence of native plants in targeted spots and then to expand their holdings. I’ve seen many successfully managed habitats where conscientious park managers diligently work and where Master Naturalists adopt certain sites and have kept on working on these sites.

In large public parks, we need some sharp-eyed and knowledgeable naturalist-volunteers to detect a new appearance of invasive plants early on to immediately eradicate them. A season or two later, they take hold and become expensive to control. We need more trained Master Naturalists to help our over-strained park managers. If you are retired or retiring and looking for doing something worthwhile, please be a Master Naturalist!

5. Our parks are seriously underfunded and under-staffed. A lot of people are wondering why park systems and park managers seem to ignore the problems of invasive plants in their neighborhood parks. The park managers are not ignoring them. The Natural Resource Protection teams have been doing extensive work to develop natural resource management plans, but they don’t have the necessary funding to implement these plans. The sad truth is that they are borrowing money to do even the basic maintenance work. In the case of Fairfax County, the Park Authority is the poorest agency whose chronic under-funding is glaringly obvious. If you want the Natural Resource Protection department have more funding so that they can implement their visions, please call your District Supervisors. They are elected officials and have the power to influence the distribution of the County’s general fund.

6. Raising concerns and communicate. Let us become the voice of natural habitats and plant communities. They struggle and quietly suffer. The nature-loving people tend to be solitary types and they don’t always raise their concerns out loud. I think, however, it is changing. We witness now more concerted efforts to protect the wild habitats among different citizen groups. We see more lively debates on best methods, more activism in general. There are also more scientific datas available, and people are busy sharing the information and pressuring the elected officials. This is hugely encouraging. I’d like to think it is not too late to reverse the trend. We can save our forests and improve their qualities.