Jerry Nissley

I recently attended a family reunion at my cousin’s restored farm house in Southampton County, Virginia. Standing sentinel to the house is a massive eastern white oak (Quercus alba) dramatically adorned with resurrection fern (Pleopeltis polypodioides). I was taken with this newly discovered (if only to me) fern and later sat down to research and write an article about the fern.

Figure 1 House and oak tree

As I fondly rehashed conversations with the four generations at the reunion about how the land was recently recovered and the house rebuilt, and then discovered facts about the resurrection fern, what was originally an article revealed itself as a story. A story not only about a fern but more so of, well, resurrection—land into a distinguished Virginia farm, a house rebuilt into a home, and the recognition of a great white oak that has witnessed 350 years of history unfold. The symbolism of resurrection was inescapable.

The story parts blend so homogeneously with the first credo FMN students are introduced to: Awareness leads to knowledge which leads to appreciation which leads to conservation.

This story is an allegory of that credo. It tells of an initial awareness of the importance of the land and ensuing knowledge of its man-made and natural elements. It represents the appreciation of the forefather’s vision in developing the homestead and the innate desire of the current caretakers to preserve structures and conserve the beauty and integrity of the land’s natural treasures. One could loosely associate Jared Diamond’s warning about landscape amnesia—where people lose knowledge of how the natural world once was, with each succeeding generation accepting a degraded environment as the status quo (Diamond, 2005). That would not be the case with these people, with this environment.

As FMNers, we all love field trips right? So please, I invite you on a short, figurative field trip. One in which we will briefly discover some Virginia history, celebrate a sentinel oak, and then explore specific details about the resurrection fern.

The House

We begin our field trip at the house in Southampton County, Virginia. The property has been in the Hart family for over 150 years and is now a registered Virginia Century Farm. Originally the farmers raised livestock on open land; rotated peanuts, corn, cotton, and soybeans to maintain soil quality; and designated large portions for timber.

Even though the property has been continually farmed by the family, as generations passed, the main house and farm buildings were at times rented out to achieve the greatest economic potential. The main house was adequately maintained, but the auxiliary buildings not so much. A few were lost to time and lack of maintenance, but the barn and blacksmith shed faired better.

My cousins, Patricia and Paul Milteer, were able to make the property their permanent home and tirelessly restored the farm house, barn, and blacksmith’s shed. They later applied to the Virginia Century Farm Program, and the farm is now officially registered by the state as The Hart Farm.

As stated on the program’s web-site, the Virginia Century Farm Program recognizes and honors those farms that have been in operation for at least 100 consecutive years and the Virginia farm families whose diligent and dedicated efforts have maintained these farms, provided nourishment to their fellow citizens and contributed so greatly to the economy of the Commonwealth.

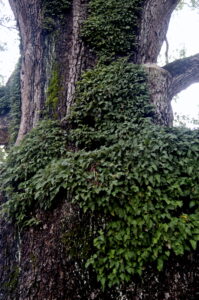

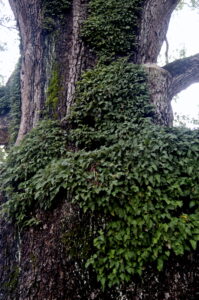

Figure 2 The Milteers’ Oak: Points: 366; Trunk circumference: 19’6”; Height: 100’; Average spread: 120’; Estimated age: 350 years

The family owners of farms designated as Virginia Century Farms receive a certificate signed by the Governor and the Commissioner of the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, along with a sign for outdoor display (Century Farms, n.d.).

The Tree

Our field trip continues just out the front door. We can sit on the porch and consider the tree. Once the house and auxiliary buildings were restored functionally and aesthetically, the Milteers were able to focus on the massive eastern white oak standing as gatekeeper to their home. The oak provides home and food to a variety of animals. A barn owl (Tyto alba) nests in the branches and bats take sanctuary in the folds of the bark.

The acorns take only one growing season to develop unlike those of the red oak group, which require at least 18 months for maturation. They are much less bitter than acorns of red oaks so they are preferred by a wider variety of wildlife. They are small relative to most oaks, but are a valuable annual food notably for turkeys, wood ducks, pheasants, grackles, jays, nuthatches, thrushes, woodpeckers, rabbits, and deer. The white oak is the only known food plant for the Bucculatrix luteella and Bucculatrix ochrisuffusa caterpillars. (Q. Alba, n.d.)

Recognizing the tree’s impressive size, the Milteers reached out to The Virginia Big Tree Program, an educational program within the Virginia Cooperative Extension that started out as a 4-H and Future Farmers of America (FFA) project in 1970. Today the program is coordinated by the Department of Forest Resources and Environmental Conservation at Virginia Tech. Their mission is to increase the care and appreciation for all trees—big and small—and educate the Commonwealth about the value of trees and forests. The Virginia Big Tree Program maintains a register of the five largest specimens of more than 300 native, non-native, and naturalized tree species. The register includes information about each tree’s size, location, and unique characteristics. (Virginia Cooperative Extension, n.d.)

Trees are ranked on a point system measuring height, crown spread, and trunk circumference. The 500-year-old national record holder for Q. alba grows in Brunswick, Virginia and scored 451 points in 2012. The next highest scoringVirginia Q. alba scored 398 (Southampton), 397 (Lee), and 396 (Albemarle) respectively. (Big trees, n.d.)

Byron Carmean and Gary Williamson, volunteers for Virginia Big Tree Program, scored the Milteer’s tree at 366, so it probably will not make the top five (maybe the top ten).

The Fern

Let’s move our field trip just off the porch to contemplate the fern. Field trips don’t get easier than this, folks!

Pleopeltis polypodioides (Andrews & Windham), also known as the resurrection fern, is a species of creeping, coarse-textured fern native to the Americas and Africa. The leathery, yellow-green pinnae (leaflets) are deeply pinnatifid and oblong. It attaches to its host with a branching, creeping, slender rhizome, which grows to 2 mm in diameter (P. Polypodioides, n.d.). The fern is facultative to North American Atlantic and Gulf Coast Plain physiographical areas.

Figure 3: Resurrection fern

This fern is not parasitic. It is an epiphyte or air plant. It attaches itself to a host and collects nourishment from air and water and nutrients that collect on the outer surface of the host. The resurrection fern lives commensalistically on the branches of large trees such as cypresses and may often be seen carpeting the shady areas on limbs of large oak trees as pictured on the Milteer’s tree. It also grows on rock surfaces and dead logs. In the southeastern United States, it is often found in the company of other epiphytic plants such as Spanish moss (Tillandsia usneoides) and is always found with some type of moss (phylum Bryophyta). The fern has spores (sori) on the bottom of the fronds and sporulates in summer and early fall (Oak and Fern, n.d.). Interestingly, rhizome sections are also viable offspring and can root themselves in new medium.

The resurrection fern gets its name because it can survive long periods of drought by curling up its fronds and appearing desiccated, grey-brown and dead. However, when just a little water is presented, the fern will uncurl and reopen, appearing to “resurrect” and restores itself to a vivid green color in as little as three hours. Studies suggest these ferns could last 100 years without water and still revive after a single exposure.

When the fronds “dry” as shown in Figure 4 (2 weeks after the reunion), they curl with their bottom sides upwards. In this way, they rehydrate more quickly when rain comes, as most of the water is absorbed on the underside of the pinnae. Experiments have shown they are able to lose almost all their free water (up to 97%) and remain viable, though more typically they lose around 76% in dry spells. For comparison, most other plants may die after losing only 8-12%. When drying, the fern synthesizes the protein dehydrin, which allows cell walls to fold in a way that can be easily reversed later (Plant Signaling, n.d.).

Figure 4 Dry fronds

Even more life, in forms that aren’t visible to the naked eye, may call the fern a community home. Stems, leaves, and flowers host microorganisms, creating a habitat called a phyllosphere, a term used in microbiology to refer to all above-ground portions of plants as habitat for microorganisms. The phyllosphere is subdivided into the caulosphere (stems), phylloplane (leaves), anthosphere (flowers), and carposphere (fruits). The below-ground microbial habitats (i.e., the thin-volume of soil surrounding root or subterranean stem surfaces) are referred to as the rhizosphere and laimosphere, respectively. Most plants host diverse communities of microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, archaea, and protists. Some are beneficial to the plant; others function as plant pathogens and may damage the host plant or even kill it. However, the majority of microbial colonists on any given plant have no detectable effect on plant growth or function. Plant phyllospheres in general are considered a hostile environment for microorganisms to live due to the variation in ultra-violet radiation, temperature, water, and nutrient contents. The phyllosphere of P. polypodioides is considered even more extreme due to the mercurial environmental conditions this epiphyte is typically found in and the dry/wet states it cycles through (Phyllosphere, n.d.).

Microorganisms do indeed survive in the phyllosphere of P. polypodioides though, even during its dry periods. In “Changes in the phyllosphere community of the resurrection fern, Polypodium polypodioides associated with rainfall and wetting”, Jackson (2006) found the micro-organism community changes as the resurrection fern moves from a dry state to wet state. Additionally, the researchers found that certain populations of microorganisms increase their enzyme activity after the fern revives. The researchers concluded that these microorganisms are responding to the secretion of sugary organics released through the plant’s surface once the fern is back to its robust, green state. Changes in phyllosphere extracellular enzyme activity are seen first as an initial burst of activity following rainfall and a subsequent burst approximately 48 hours later as additional nutrient sources emerge.

Figure 5 Revived fern

Cultural studies have shown that Native peoples historically recognized the significance of the resurrection fern. It has been used as a diuretic, a remedy for heart problems, and as a treatment for infections. Benefits of the resurrection fern are not lost on the modern pharmaceutical industry. Recent medical research confirming these cultural reports have shown that extracts from the fern have anti-arrhythmic cardiac properties—truly a potential for resurrection of the heart.

Figure 6 Resurrection Fern up close

Thanks in part to the training provided by dedicated FMN program instructors, in this case our resident dendrologist Jim McGlone, I am aware of trees like never before. I see trees, I see what lives in trees, I see ferns, and I see the need for conservation. What I need to see more clearly and we all need to experience is the indelible, spiritual, personal relationship people need to have with nature. People are the caretakers of the gifts we have been given on earth, and people need to be the stimulus for conservation. As John Muir (1911) elegantly journaled, “How fine Nature’s methods! How deeply with beauty is beauty overlaid!” It is inspiring to me that something as small as a fern encouraged awareness, understanding, appreciation and, yes, resurrection of “nature’s fine methods”.

Works Cited

Big trees. (n.d.). Retrieved from www.americanforests.org: www.americanforests.org/get-involved/americas-biggest-trees/bigtrees-search/bigtrees-advanced-search/

Century Farms. (n.d.). Retrieved from www.vdacs.virginia.gov: www.vdacs.virginia.gov/conservation-and-environmental-virginia-century-farms.shtml

Diamond, J. M. (2005). Collapse: How societies choose to fail or succeed. New York: Viking.

Jackson, E. F. (2006). Changes in the phyllosphere community of the resurrection fern, Polypodium polypodioides, associated with rainfall and wetting. FEMS microbiology ecology 58.2, 236-246.

Muir, J. (1911). My First Summer in the Sierra. Boston: Houghton Miffin.

Oak and Fern. (n.d.). Retrieved from www.sciphotos.com: www.sciphotos.com/2016/01/oak-tree-resurrection-fern.html

P. Polypodioides. (n.d.). Retrieved from en.wikipedia.org: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pleopeltis_polypodioides

Phyllosphere. (n.d.). Retrieved from en.wikipedia.org: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phyllosphere

Plant Signaling. (n.d.). Retrieved from www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3256378

Q. Alba. (n.d.). Retrieved from en.wikipedia.org: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quercus_alba

Virginia Cooperative Extension (n.d.). Virginia Big Tree Program. Retrieved from ext.vt.edu: http://ext.vt.edu/natural-resources/big-tree.html